「君たちはどう生きるか」の意義

米映画界の最高峰、アカデミー賞を受賞した宮崎駿監督(83)の長編アニメ「君たちはどう生きるか」は、太平洋戦争中に火事で母親を亡くした少年の心の葛藤を描いた。「困難で激動の今の時代に対し、強く問いかける傑作だ」。米国でジブリ作品を研究する第一人者の米タフツ大のスーザン・ネイピア教授 Susan Napier(68)は、世界で戦争が続く中での受賞を「痛切な意義がある」と評した。2001年9月11日の米中枢同時テロ後の価値観の変化を指摘する。「残念だが、世の中はハッピーエンドでは終わらない、善人が勝つとは限らないという大きな警鐘になった」。9.11以降、宮崎監督が描き出す複雑で矛盾に満ちたリアルな世界観が若者を中心に共感を呼んでいるという。

解説

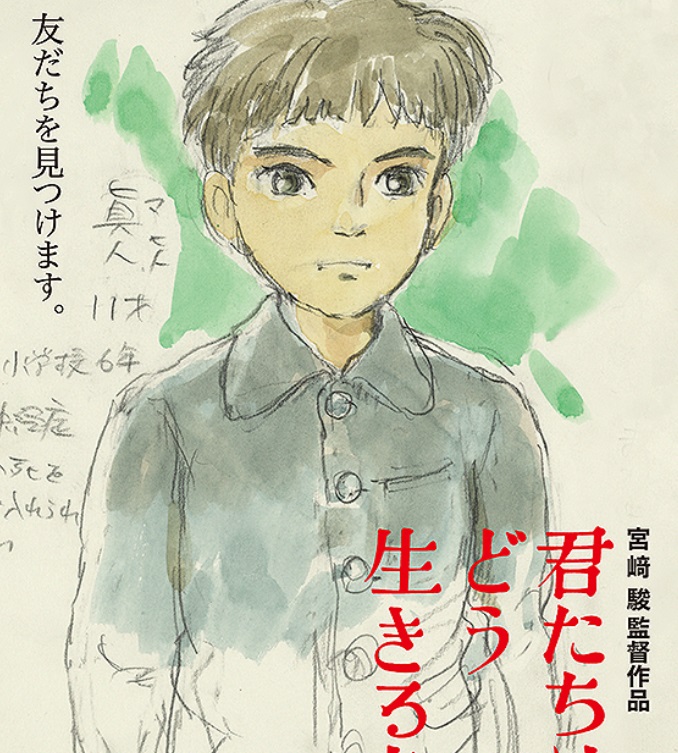

宮崎駿監督が2013年公開の「風立ちぬ」以来10年ぶりに世に送り出した、スタジオジブリの長編アニメーション。「風立ちぬ」公開後に表明した長編作品からの引退を撤回して手がけ、宮崎監督の記憶に残るかつての日本を舞台に、自らの少年時代を重ねた自伝的要素を含むファンタジー。母親を火事で失った少年・眞人(まひと)は父の勝一とともに東京を離れ、「青鷺屋敷」と呼ばれる広大なお屋敷に引っ越してくる。亡き母の妹であり、新たな母親になった夏子に対して複雑な感情を抱き、転校先の学校でも孤立した日々を送る眞人。そんな彼の前にある日、鳥と人間の姿を行き来する不思議な青サギが現れる。その青サギに導かれ、眞人は生と死が渾然一体となった世界に迷い込んでいく。

宮崎監督が原作・脚本も務めたオリジナルストーリーで、タイトルは宮崎監督が少年時代に読んだという、吉野源三郎の著書「君たちはどう生きるか」から借りたもの。アメリカでも高い評価を得て、第81回ゴールデングローブ賞では日本作品で初めてアニメーション映画賞を受賞し、第96回アカデミー賞でも宮崎監督作およびジブリ作品として「千と千尋の神隠し」以来となる2度目の長編アニメーション賞受賞という快挙を成し遂げた。2023年製作/124分/G/日本 配給:東宝 (映画.com「オッペンハイマー」) Oppenheimer Official Site(日本語予告編)

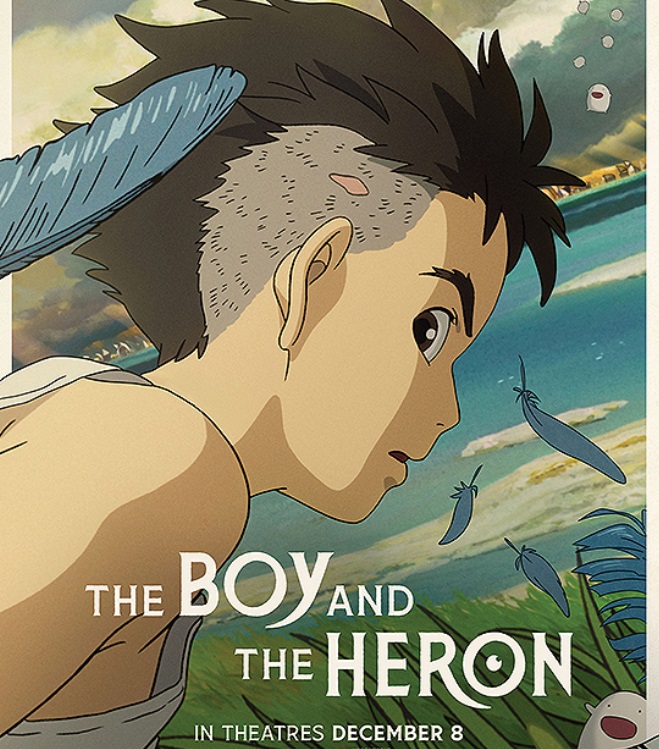

In a ‘vast and limitless world’: the grieving Mahito Maki encounters some ‘beaky interest’ in The Boy and the Heron. by The Guardian

The Boy and the Heron review – overplotted Miyazaki still delights /This article is more than 2 months old

At 82, the revered director of Spirited Away and My Neighbour Totoro has made his most personal film yet – a sometimes unwieldy tale of a 12-year-old boy coming to terms with his mother’s death

It’s the film that the revered animator and co-founder of Studio Ghibli Hayao Miyazaki came out of retirement to make, and it’s arguably one of his most personal. The Boy and the Heron is a strikingly beautiful, densely detailed fantasy that revisits themes and devices familiar from previous films and ties them together with elements that have a clear autobiographical resonance for the director. The dream logic of the narrative seems to have been born from the untrammelled imagination of a child rather than that of a man in his 80s. The lush orchestral score, by regular Miyazaki collaborator Joe Hisaishi, is shimmering and exultant. All the elements are in place. So it seems almost churlish to note that this is middling Miyazaki at best.

Of course, a mid-level Miyazaki film is still a vastly superior entity to much of the more cynically commercial content served up by Hollywood animation studios. And it’s not as if the seductive spell has been entirely broken. But compared with, say, the beguiling simplicity of My Neighbour Totoro, or the richly realised world of Spirited Away, this sometimes feels heavy going. Some of that trademark Miyazaki magic has been stifled by overplotted, incoherent storytelling and an unwieldy final third act.

The backdrop, for some of the picture at least, before it slips into parallel realms, is early 1940s wartime Japan. The boy of the title is 12-year-old Mahito (voiced by Soma Santoki in the Japanese original version and Luca Padovan in the impressive English-language dub). Shortly before the main action takes place, Mahito loses his mother in a hospital fire after a bombing raid on Tokyo. The inferno engulfing the city has a disorientating, impressionistic quality that’s distinct from the precise visual style of the rest of the film, and this striking image of a burning city is one that Miyazaki has cited as one of his earliest childhood memories.

Mahito’s father is the boss of a factory that manufactures fighter planes (as was the director’s own father). He remarries, to his late wife’s younger sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura/Gemma Chan), and the still grieving Mahito is forced to relocate from Tokyo to the country estate where his mother and Natsuko both grew up. It’s a curious, cavernous place, populated by a staff of bickering, ancient crones; it comes with a lake and a bricked-up, semi-derelict tower in its grounds.It also has another resident: an insolent grey heron (Masaki Suda/Robert Pattinson) that seems to be taking a particular beaky interest in Mahito.

At the goading behest of the heron, Mahito enters the forbidden tower and finds himself drawn into a netherworld where timelines are knitted together and the infrastructure of the whole domain is controlled by some kind of high-stakes Jenga game. Fellow inhabitants of this world include Kiriko (Kô Shibasaki/Florence Pugh), a dashing sailor and fisherwoman who is skilled in magic, and the fire maiden Himi (Aimyon/Karen Fukuhara), as well as Mahito’s new stepmother, Natsuko, and a community of giant man-eating parakeets.For a director who is so famously preoccupied with the idea of flight, Miyazaki reveals an unexpectedly complicated relationship with birds in this picture. In addition to the monstrous parakeets that eye Mahito greedily, cutlery at the ready, there is also a flock of pelicans that feed on gentle floating creatures called the Warawara. And then there’s the heron, which soon loses its elegant avian form and morphs into one of Miyazaki’s less lovely creations, a wart-encrusted, goblin-like henchman in service to the ruler of this magic kingdom – an ageing wizard who, it turns out, has a connection to Mahito’s family. Ultimately, family – even a fractured, imperfect family scarred by loss – is elevated, forming the central spine of this picture, as it does in so many of Miyazaki’s movies.